The 125-year-old Rhode Island lager is having a comeback and is now winning over New York’s cool kids

When Mark Hellendrung bought the Narragansett beer company in 2005, close to nobody drank the 125-year-old New England lager.

Gone were the glory days of the 1960s, when the beer was the official sponsor of the Red Sox, produced up to two million barrels a year, and ran its brewery at close to capacity to meet demand. Narragansett so symbolized New England that eccentric shark hunter Quint in Jaws literally crushed it in a now iconic scene.

“Narragansett was New England, and New England was Narragansett,” Hellendrung says of the beer’s boom years. “It had a 65 percent market share, and it was a part of the very fabric of New England.”  The brand brewed fewer than 600 barrels in 2004 and the next year, Hellendrung, a former president of Nantucket Nectars, bought it from Pabst Brewing Co. for an undisclosed amount.

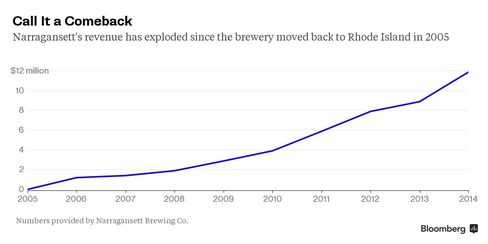

Now the native Rhode Islander can be proud of his regional beer again. Narragansett produced 78,034 barrels in 2014, according to the company, and pulled in $12 million in revenue, up from just $100,000 in 2005. In 2013, it cracked the Brewers Association’s top 50 breweries in the U.S., based on beer sales by volume, for the first time ever. It jumped another 12 spots last year, to No. 37.

About a third of Narragansett’s sales now come from outside New England (the company is based in Providence), and it is becoming a popular alternative to Pabst Blue Ribbon among price-sensitive beer drinkers at hip Brooklyn bars. It was the cheapest of the top four fastest-growing beers in Brooklyn in the past year, according to GuestMetrics, which tracks 415 or so beer brands at 18 locations in the borough. It was trumped only by Allagash, Bell’s, and Blue Point, three craft beers that can sell for almost twice as much as Narragansett. “When we opened about two years ago, it was making a huge stomp on Brooklyn,” says Adam Bohanan, a bartender at Brooklyn’s Brew Inn, which sells Narragansett for $3. “Everybody was ordering it, everybody wanted it. So we decided we would have it as well. We don’t want to be behind the times.”

A mild American-style lager, Narragansett is not so different from PBR or Budweiser: It has 5 percent alcohol content, like Bud, and in New York City generally goes for $4 to $6 for a 16-ounce can. PBR is around $3 to $4 for a standard 12-ounce can. “When we first opened, nobody knew what [Narragansett] was, and the number of mispronunciations of the name was as many as got it right,” says John McWilliams, the bar manager at Burnside, a Williamsburg bar that sells the 16-ounce Tall Boys for $4. “Now people come in and ask for ‘Gansett.” McWilliams sells “a ton” of it, he says.

Apart from being cheap, Narragansett has hit its stride by making a play for young drinkers who like smaller craft breweries. “In the early days we chased some of that college business. It’s just not the right way to build a brand,” says Hellendrung. “In a lot of ways they’re white elephants. Yeah, they drink a lot of beer; they don’t care what’s on the can.” Light offerings from Big Beer—the Coors, Bud and Miller Lites of the world—has seen an 8 percent decline in sales since 2008, according to research by Impact Databank. “It’s urban, cities, craft-beer drinkers,” says Hellendrung of his customer. “And not so much blue collar, brain-washed Bud drinkers.”

When he bought the brand in 2005, Hellendrung first turned to Narragansett’s brewmaster from 1967 until 1975, Bill Anderson, who tweaked the recipe to add more hops and a maltier flavor. A 2013 survey by ConsumerEdge Insights found that 27 percent of consumers who are opting out of light beer said the main reason is “getting tired of the taste.” “In 2004 [Narragansett] was a very watered-down beer,” Hellendrug says. But he didn’t want the new taste to be too potent. “When you’re sitting down having a bunch of beers at a BBQ, you can drink only so many 58 IBU, 8 percent-alcohol beers before your pallet is just cooked.†Narragansett scores 77 out of 100, or fair, on Beer Advocate, a site that crowdsources reviews, while PBR gets 68 out of 100 (poor). Deadspin also put Narragansett second on its rankings of cheap American beers, beating PBR, which was 5th. The changes Anderson made also affected the color of the brew. “It’s an aesthetic thing,” says Bohanan. “It actually looks slightly darker than PBR. People see that, and they’re like, ‘oh, it’s a darker beer, and darker beers are normally better.'”

Looks and taste aside, Hellendrung has also tapped Narragansett’s 125-year-old history to appeal to the younger, hipper crowd. Millennials love nostalgia and heritage brands. “Everything we try to do is bringing Narragansett back to life through a historical lens, in a contemporary context,” Hellendrung says. For the past two summers, the brewery has released a limited-edition can design to commemorate its cameo in Jaws and has also teamed up with beloved Rhode Island brand Del’s for a beer lemonade shandy and century-old Autocrat Coffee for a milk stout.

“Heritage brands of beer are gaining a lot of interest,” says Julia Herz, the craft beer program director at the Brewers Association. “Beer companies that have a niche are going to find that sharing their story with the beer lover, and the history, and the heritage, and the intention behind the brand, are going to help them get traction.”

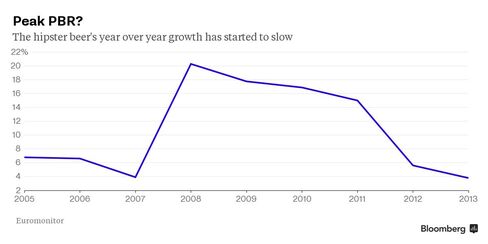

Narragansett is trendy in the North East but far from taking PBR’s crown as king of cheap hipster beers across the U.S. Although growth is slowing for PBR, it still sold 374 million liters nationwide in 2014, according to Euromonitor. Narragansett sold just 9 million liters and hasn’t made much of a dent outside its surrounding regions. More than 80 percent of Narragansett’s sales come from the D.C., Philadelphia, New York City, Providence, and Boston metropolitan areas, per GuestMetrics.

However, owning a niche might be more important for a beer’s success in today’s increasingly fragmented drinking culture. A Neilsen survey in February found that a majority of the 21 to 34-year-old beer drinkers surveyed cited buying local as very or somewhat important.  While a New Yorker might pick up a Narragansett or a Sixpoint, drinkers out West are guzzling Session Lagers or a Green Flash IPA. “With the number of brewing companies these days, differentiating yourself is more important than ever,” says Bart Watson, an economist at the Brewers Association. His colleague Herz agrees: “The beer category is no longer one beer brand and one beer style.” A single beer might never again dominate.

See full article at: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-06-12/how-narragansett-became-cool-again